Fan or Client? The Album Variant Epidemic

I thought the end of The Eras Tour would mean the end of Taylor-mania. Then The Tortured Poets Department happened, which I figured had to be the peak. Now The Life of a Showgirl is here, and thirty-four variants later, I think I’m the one being tortured.

Credit: Variety

Every time I open my timeline, there’s another variant—a new cover, a new vinyl color, a new “exclusive” acoustic or voice note. My feed looks like a digital museum of glitter and heartbreak. Half the time I can’t even tell what’s a deepfake and what’s real anymore.

Being a Swiftie in 2025 feels less like a fandom and more like record-keeping. We’re cataloguing colors, tracking drop dates, archiving merch codes like it’s pop culture anthropology. Somewhere along the way, the excitement started fading.

We as fans stopped feeling thrilled about the drops because they never stop—they just pile up. It’s like being force-fed as a fan: there’s always another edition, another demo, another vinyl color. It’s so much, it’s grotesque.

There was a certain moment where fans collectively realized, oh. This is a business. Thirty-six variants can’t possibly all be about artistic expression—at some point, you’re just shamelessly milking your fan base.

For Gen Z, it’s been a rude awakening. We grew up believing music was about connection, not corporate strategy. We believed our favorite artists spoke to us, saw us, chose us. But now, as streaming flattens the value of music and physical sales turn into collectibles, those same artists are turning their discographies into limited-edition stock.

New covers, new vinyl colors, bonus voice notes—it’s not just about listening anymore. It’s about owning. And that’s when it gets too obvious: maybe we’re not fans anymore. Maybe we’re clients.

The Variant Club

Taylor may be the queen of the variant economy, but she’s hardly alone.

Olivia Rodrigo’s GUTS (Spilled) came with four differently colored vinyl variants, each with a brand new hidden bonus track, and each promising a different kind of angst.

Billie Eilish’s Hit Me Hard and Soft joined the wave with recycled-material pressings and limited runs. At least Billie tried to soften the blow by making sustainability part of the brand. It’s capitalism, but make it conscious.

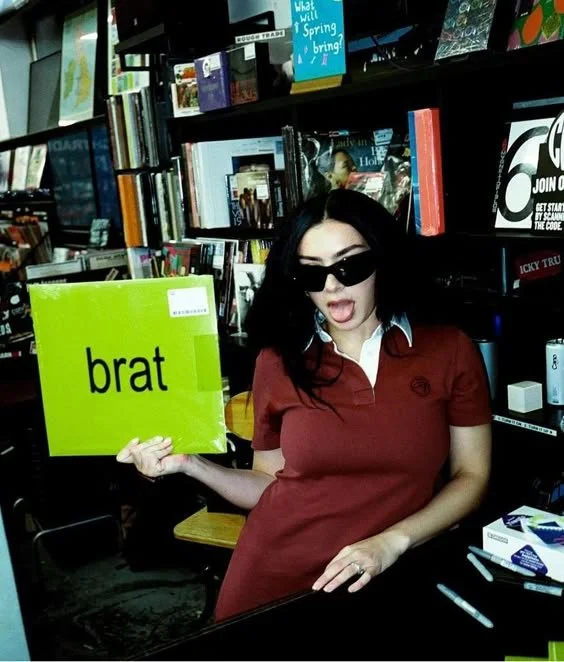

Charli XCX, chaos angel of hyper-pop, handled it differently. Brat didn’t just get slapped on ten colors of vinyl. She dropped remix editions, new features, and reworks that actually added something. She saw her big break and stretched the moment—and honestly, we said thank you and blasted 360 all summer.

Credit: The Central Trend

Not all variants are created equal. Some expand the art; others just expand the cart.

Why Artists Do It

“Streaming broke everything” is what people say, but it’s deeper than that.

Streaming made music infinite—and in doing so, it made it feel disposable. When every song you’ve ever loved is one tap away, albums stop feeling like prized objects and start feeling more like just another playlist in your library.

People used to raid record stores on album release days; now, you just throw an album listening party from the comfort of your house and press “play” when the clock strikes midnight, if you’re feeling extra. For artists, that’s a big problem because (surprise) streaming pays pennies. Spotify, for instance, reportedly pays artists about US$0.00348 per stream. According to GMA, The Life Of A Showgirl gained 1.5 billion streams in its first week. Do the math, and that’s roughly US $5.2 million from Spotify alone—impressive, sure, but once you subtract marketing budgets, label cuts, production costs, and rollout expenses, the number keeps shrinking.

Why We Keep Buying

So for artists, the math still matters. Streams bring exposure, not security. A viral TikTok doesn’t pay rent. A hit tweet doesn’t fund a tour.

Zara Larsson knows this all too well. After opening for Tate McRae across the U.S., she went viral on TikTok for her electric stage presence—but the attention quickly turned messy. Fans began pitting the two singers against each other, using Zara to critique Tate in comment sections and stan wars. When Midnight Sun, Larsson’s fifth studio album, finally dropped, Zara noticed something strange: the same people praising her online weren’t actually supporting her offline. The album debuted at #119 on the Billboard 200, with 11,000 copies sold. “It’s been so many hit tweets and TikToks,” she said. “And I’m like, buy the album! It just doesn’t make sense.”

Her comment wasn’t just about sales—it was an epiphany. The people boosting her online weren’t fans, they were participants in senseless spectacle. They didn’t want her music, they wanted a moment. She realized a true core in the business: attention is not attachment. Getting people to go out of their way to buy your music, when they don’t need to. That’s power.

And that’s where Taylor has the upper hand. She doesn’t just release music; she maintains a relationship. Swift has built a feedback loop of parasocial loyalty so strong that fans don’t just stream her, they invest in her. They’ll buy ten variants of the same record because it feels like supporting a friend, not a brand.

Virality doesn’t equal sales anymore, and fame doesn’t equal financial success. But connection? That still converts.

Credit: @1989vinyl on Tiktok

In a now deleted post, activist and creator Matt Bernstein recently said:

“Swifties please do not hurt me when I tell you this woman is financially exploiting the parasocial relationship she and her team have gone painstaking lengths to create with you. It just hurts to watch.”

The post sparked backlash and harassment, but it also hit a nerve. Many fans recognized the uncomfortable truth in it: this kind of rollout depends on devotion. It depends on fans who will buy anything their idol offers. It’s not out of greed, but love. Out of “she was there for me when no one else was.”

Taylor’s direct line to her fans has always been the cornerstone of her empire. Long before The Eras Tour, she hosted meet-and-greets but never charged for them. While other artists charged thousands for backstage passes, she hand-picked fans from the crowd and invited them herself. Later, she formalized that intimacy through Secret Sessions, inviting small groups of fans she had personally “taylurked” on online to her homes to preview her albums.

These gestures of closeness built more than loyalty; they built expectancy. Fans began to believe that devotion might be noticed, that if they loved hard enough or posted often enough, they could be chosen next. What began as authentic connection slowly turned into anticipation, a sense that being a “good” fan might one day pay off.

When artists lean directly on that intimacy to move units, handwritten notes, voice memos, “this edition is for the people who really understand me”—it slides from marketing into emotional manipulation.

For the devoted, it’s dopamine and rush. For everyone else, it’s fatigue. You may get the creeping sense that your favorite artist’s “thank you for supporting me” is now code for “your wallet, please.”

But not every artist is going to be able to replicate this model, because what makes it work is longevity. Most of us have quite literally grown up alongside her music. She soundtracked our lives. Each album holds a piece of time: a party, a heartbreak, a friendship, a fight. Taylor Swift has been in the public eye for twenty years, and she’s still at the top. That kind of stability is almost unheard of, only comparable to Beyoncé. Most artists fade. Fans want something new, trends move faster than release cycles, and attention spans keep shrinking. But Taylor evolved with her audience. Her sound, her image, even her marketing matured in sync with her fans’ own coming-of-age. For many Swifties, our relationship with her, as parasocial as it may be, is the longest and strongest one we’ve ever had. That’s what drives this business model: history. And that’s exactly why no new artist could replicate it. You need time. You need to become a constant in people’s lives, so present that they can’t imagine their lives without you.

It’s also worth remembering that every artist has their thing, and for Taylor, that’s songwriting. She’s said it herself: she probably wouldn’t even be a singer if she couldn’t write songs. And that’s the key to her longevity. Songwriting is elastic; it grows as you do. Twenty years ago, she was writing about high school crushes and small-town heartbreak. Now she’s writing about thinking of marriage, legacy, and what it means to be known. Her lyrics evolve because her life does, and her fans evolve with her. Even those outside her age group can still trace the story of her life through her music. That’s the power of storytelling. Taylor Swift as an artist, a brand, and a business runs on narrative continuity. Every album feels like a new chapter, every relationship like a subplot. To many, her engagement to Travis Kelce isn’t just tabloid gossip; it’s the story’s full-circle moment, the “end game” her fans have been waiting for.

Fan or Client?

Maybe this is what fandom means now: loving the music while distrusting the selling machine behind it.

Pop once promised intimacy—that sacred loop between artist and listener. But in the variant era, that loop has been priced. It’s no longer about who an artist is to us, but how many editions we’ll buy to prove it. So sure, buy the orange glitter vinyl if it makes you happy. Display it. Frame it. Just don’t mistake it for love.

As I’m finishing this article, my phone lights up:

“Greetings, showgirls! The Fate of Ophelia (Alone In My Tower Acoustic Version) can now be yours to download…”

Of course it can. The variant era keeps performing, even when no one’s asking for an encore.